Can vegans eat avocados? Avocados are plants that grow on trees for humans and non-humans to eat. By this logic, avocados are vegan-friendly.

However, vegans don’t consume honey due to the unnecessary exploitation of honeybees. These same bees are often migrated across countries in less than ideal conditions to pollinate large crops of avocados so that we can enjoy our avo on toast in peace. So, it’s argued that avocados like honey aren’t vegan.

In this article, we explore the ethical dilemma of supporting the avocado industry. Even though we’re focusing on avocados, the same principles apply to other resource-heavy crops like almonds.

Specifically, we discuss the size of the avocado market, migratory beekeeping practices, and the edges of veganism before finishing with some actionable tips when trying to buy avocados with the least impact.

How big is the avocado industry?

The global avocado market is valued at over 12.8 billion dollars and is expected to grow to 17.9 billion dollars by 2025. The growth was triggered by increased awareness of avocado health benefits and a rapid cultural adaption by millennials.

The largest producer of avocados is Mexico, accounting for 34% of the global market, while the biggest importer is North America, representing a whopping 52% of all global imports. Here’s how North America stacks up against the rest of the world:

| Region | Percentage of global imports |

| North America | 52% |

| Europe | 33% |

| Asia | 7% |

| Rest of the world | 8% |

The numbers are pretty staggering. But how do we go from a humble fruit tree to producing them at such a scale? We first need to understand the process of harvesting avocados.

The challenge with growing avocados

Avocados, also known as the ancient Mexican fruit, originated from South America. They’re a finicky tree that prefers warmer, consistent climates—although many varieties are successfully grown worldwide.

From seeds, avocado trees can take anywhere between 10 and 20 years to mature and bear fruit (if you’re lucky). The infant tree is thirsty—requiring 270 litres of water to produce one pound of avocado fruit.

Avocados require perfect drainage and elevation, as they don’t like to have wet roots.

When it comes to pollination, avocado trees are unique from other fruit trees. There are two types, type A and type B.

Both varieties consist of flowers that open once as a male, close, then open again as a female flower. A and B type trees tend to have alternating schedules in the morning and afternoons, which normally means that growers have two avocado plants to achieve cross-pollination.

In cooler climates like New Zealand, avocado flowers open in the evenings, so they rely on nocturnal pollinators like moths and bats.

To make matters difficult, honeybees are not the biggest fans of avocado flowers and will usually skip over them, searching for a more desirable nectar source.

Some growers spray their flowers with a formula that includes honey and water to entice bees to pollinate the avocado flowers.

In contrast, tomato and chilli pepper plants can easily self pollinate through either the wind or the vibration of animal pollinators, including bees, flies, butterflies, and hummingbirds, to name a few.

Depending on the climate, avocados are harvested every second year in the spring and summer.

Due to the complex process of growing avocados, commercial growers manipulate their farming practices, including bringing in boxes of honeybees to help pollinate the flowers.

What is migratory beekeeping?

There are generally two types of beekeeping; backyard or hobbyist beekeeping and commercial beekeeping. The primary motivations for both approaches are to produce honey, beeswax and pollinate flowers.

Backyard keepers manage one to a few hives as a passion project and sometimes profit from their honey.

Commercial beekeepers carry tens to thousands of hives at any given time with the purpose of profiting from honey production.

However, another type of beekeeping has a significant impact on the foods we consume, and that’s migratory beekeeping.

Migratory beekeeping is managing large volumes of beehives, using the bees to pollinate vast amounts of crops in a geographic area.

Farmers pay migratory beekeepers up to USD 200 per hive to pollinate their crops. This exchange is referred to as a “pollination rental.”

Migratory beekeepers view their bees as livestock animals put onto trucks to go and pollinate crops across the country. For example, in February each year, over 31 billion European honeybees are trucked into central California to pollinate hundreds of billions of almond flowers.

These ginormous almond orchards are responsible for up to 80% of the world’s almonds.

The bees hit the road again, offering up their pollination services for blueberries, avocados, apples and many other crops across the United States.

Then, once the crops have bloomed, the same bees are used to produce honey, ensuring they’re productive all year round.

This story isn’t unique to America. Here in Australia, commercial beekeepers diversify their income beyond honey by offering pollination services. The company Goldfields Honey moves 5,000 hives to almond plantations on the Murray River each year.

A combination of fatal diseases such as colony collapse disorder (CCD), pesticide exposure, the stressful travel conditions from being on trucks, the restrictive diet, winter, and the lack of nectar available compared to the number of hives kept for honey production; keepers can lose anywhere between 30-70% of their hives each year. That’s an alarming rate of death for these hard-working bees.

Migratory beekeepers, like any farmer, factor in losses and put contingencies in place to create more colonies by splitting healthy beehives in half. This is an effective process to grow stock levels and sometimes increase hives year on year.

Read more: Is Honey Vegan? The Definitive Guide

Is migratory beekeeping vegan?

Migratory beekeeping is a farming approach where bees are bred and exploited for their pollination services and honey production for human consumption. Many bees die in the process, and when assessed in isolation, the practice of migratory beekeeping is unethical and not vegan.

However, when we take a step back and look at the totality of crop agriculture, there’s much more to consider.

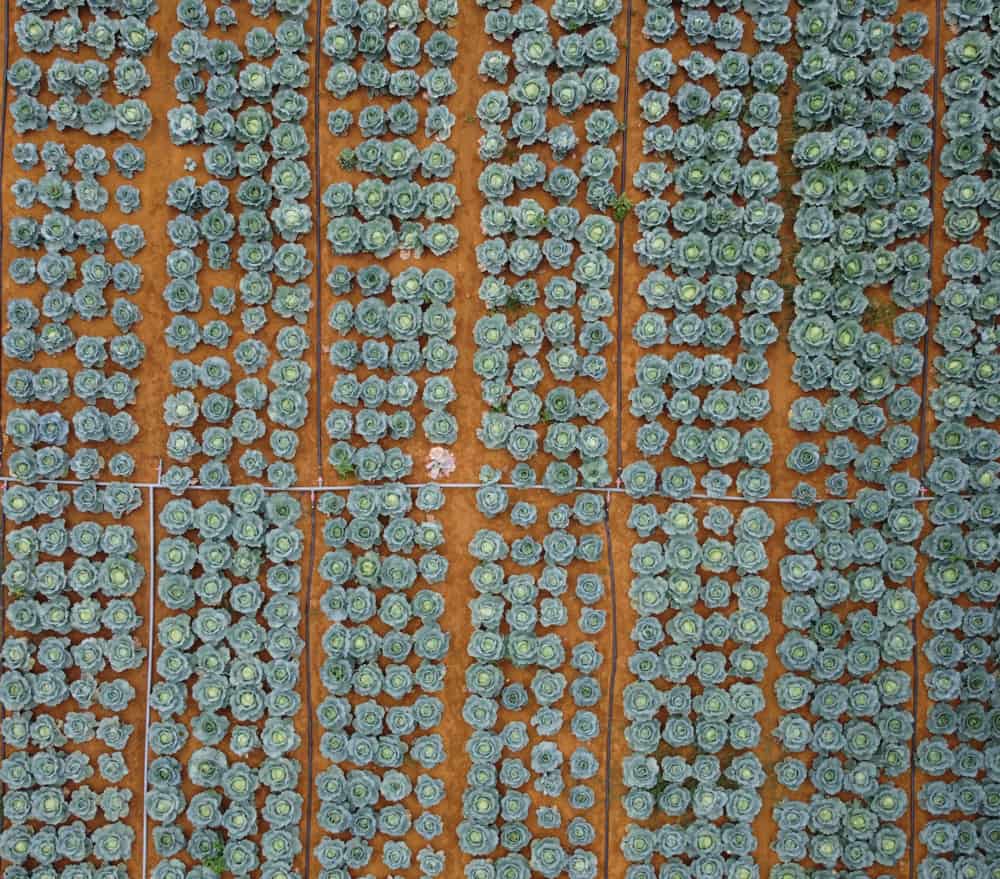

Let’s start with monoculture, an agricultural practice of growing a single crop or livestock species to improve farming efficiency. Think large scale chicken farms or blueberry orchards with no diversity.

While economically, monoculture is profitable and effective in producing more food for the masses, it’s about as far away from nature as we can get.

Animals and plants are biologically designed to co-exist together, not in isolation. This is why monocropping leads to more pests, disease and, of course, migratory beekeeping.

We must remember that honeybees are one of over 20,000 bee species originally imported from Europe for their productivity and honey. Not to mention all the other animal pollinators.

On the other hand, polyculture is an agricultural approach where more than one species of crop and animals are farmed to mimic natural ecosystems.

While polyculture farms are not always lush wild gardens attracting all the native pollinators in the area, it’s still a more environmentally and vegan-friendly system than monoculture. That’s because polyculture farms are less dependent on migratory bees, as the variety of crops attracts natural pollinators.

If you can, support farms that aren’t dependent on pollination rentals due to monocropping, as they’re generally vegan. This brings me to the next point…

Is there anything we consume technically vegan?

To understand if it’s okay for vegans to eat avocados and other crops pollinated by migratory bees, it’s critical to revisit the intent behind veganism.

Veganism is about doing everything you practically can to avoid the harm and exploitation of animals. The definition of veganism extends to how we treat humans as well.

Non-vegans routinely call out vegans for their hypocrisy for not eating honey. It goes something like, “well, if you don’t eat honey, are you prepared to give up almonds?” For the reasons laid out above, the question is valid.

Vegans will respond by quoting the definition of veganism, suggesting that veganism isn’t about being perfect, but it’s better for the animals if we do everything that we practically can. Besides, we have to eat, right? Again, another good point.

To take this a little further, virtually everything we consume has an indirect impact on another animal.

Walking outside means unknowingly stepping on insects. Or perhaps you’ve been in the dreadful situation of accidentally hitting an animal with your car. It’s a horrible feeling, I know.

Some countries test the quality of drinking water on specific fish species to see if there are any poisons or harmful chemicals.

What about organic cotton? Another popular monocrop that’s likely pollinated by migratory bees.

We unknowingly kill flies when they get trapped inside our homes.

I’ve probably eaten my share of small caterpillars hiding in my broccoli.

I could go on all day.

Where do we draw the line? Do we stop eating, sleeping, driving, and wearing clothes? What is the edge of veganism? That’s probably something only you can answer.

However, don’t cop out and think that eating lamb this afternoon is the best you can practically do; therefore, you’re vegan—unless that’s the only food you have access to (highly unlikely if you’re reading this).

Buying animal products or paying for animal entertainment is still directly linked to killing or exploiting animals. We can do better than that. But not drinking water because we’re unsure of the source? That’s where things get ridiculous. Logic applies here.

But if you’ve made it this far in the article and are freaking out if you can eat avocados or not, read on.

What are the most ethical options for buying avocados?

Vegans can eat avocados, but like any product, there’s a sliding scale of impact. Below are five options for buying avocados, ranked by the most vegan-friendly to the least vegan-friendly. The same hierarchy can be applied to any plant foods.

Best option — backyard avocado trees

Do you know someone in your area who happens to have a productive avocado tree? Outside of growing your own avocados, buying from your neighbours is going to be the most ethical option.

It’s improbable that you’ll know someone who has an avocado tree, and if you do, you’ll have to adjust to eating it seasonally.

Another option is to check if you have a local food co-op in your area selling avocados. That way, you know, folks have brought in their fruit to contribute to the broader community.

2nd option — local avocado farmers

If you can’t find avocado trees in your town, the next best option is to purchase avocados at your local farmers market. Local farmers usually have diversity in their crops, attracting natural pollinators.

As an added benefit, you get to support the local economy and build relationships with the people growing the food you enjoy. Like backyard avocados, you’ll need to get used to eating fruit seasonally and not all year round.

Keep in mind that some local farmers will still shoot pests, use pesticides, kill critters or use soil mixtures that include dead animals. Again, that doesn’t mean it’s not vegan, but it’s something to be aware of nevertheless.

3rd option — large scale polyculture farms

The next best option after farmers markets is to purchase avocados produced on large polyculture farms.

You’ll normally find these avocados at your organic grocers, health food stores and bulk stores.

Out of all the options, this is the hardest one to find information about and will likely require some investigation.

Start by asking the shop assistant if they know their supplier directly or at least have a contact. From there, you can ask if the farm only specialises in avocados or if they have other crops on the farm. You can also ask them directly how they pollinate their food.

If you do the digging and get the answers, be sure to share your findings with your community.

4th option — national commercially sourced avocados

Okay, now we’re getting into the supermarkets. This is how most of us access avocados all year round.

At this point, it’s pretty safe to assume that avocados in supermarkets are produced using migratory bees due to monocropping practices.

This isn’t ideal, but it’s also the only option for many of us. Only you can decide if you’re comfortable purchasing avocados at this level.

You also want to ensure that the avocados are produced in your country.

5th option — imported avocados

The least ethical and sustainable option is buying imported avocados from your supermarket. These avocados are grown and harvested at a massive scale in monocultural environments, and then transported across the globe.

What’s worse is that some of these farms exploit their workers by underpaying them to pick avocados.

You can tell where avocados are from by reading the little stickers on them or the general signage in the supermarket.

This is the last resort if you’re considering buying avocados. Again, the choice is yours but understand the impact.

So, what do you think? Can vegans eat avocados?

The exercise of questioning the ethics of the food we consume is valuable when reducing your impact.

Yes, it can mean more work and less convenience. But by educating ourselves, we can make better choices. Not perfect, but better.

Now I’d love to hear from you. Do you think buying avocados is vegan?

knowing that the foods you mentioned are necessary and are for pure taste-pleasure, why not just avoid them to play it safe?

Thank you for your thoughtful article. A similar situation I have come across is our locally grown hot house tomatoes. Last year I went on a tour of a tomato greenhouse and learned that they purchase bumblebees to pollinate the hothouse tomatoes. It is concerning to see how animals lives have been incorporated at almost all levels of food production.

I’m so glad to hear that, Amit! I hope you have a small support network as you make the switch. And yes, there are always things to consider with everything we consume. It’s the inconvenient truth. All the best.

I really love reading this. Thank you for laying out the logical, the important, and the steps one can take. So helpful for us to ponder.

I’m glad you found value in the post, Kristen. Thanks for reading and being open.

Great article, thanks. It’s easier for us (Australians) to only eat avocados grown in our own country, the only decision to be made is whether to buy New Zealand avocado which turns up occasionally. Much harder if you live in the UK (for example) as I don’t expect they don’t grow any.

Thanks, Jillo! Yes, location is always going to play a role. I’m not sure how avocados are farmed in the UK but reading the comments in this article, it certainly seems possible.